Women’s Clubs and Suffrage

After the Civil War, the number of women’s clubs exploded. Women organized clubs around a variety of causes and interests. They learned how to operate as a group for a cause. They joined clubs like the National Federation of Women’s Clubs, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, and the National Council of Jewish Women, which gave them access to new ideas and contacts across the country.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) worked to strengthen family life by avoiding alcohol. They saw alcohol as the root of suffering for women and children. The WCTU also worked for prison reform and labor laws. The organization was most powerful from 1879 to 1898, under the leadership of Frances Willard. Support of woman suffrage caused controversy, and after 1900, it focused on prohibition.

The different suffrage groups often found it hard to mobilize both women and men in favor of woman suffrage. Women cycled in and out of the movement as their life circumstances and interests changed. After 1900, some of Minnesota’s early suffragists were still active. Among them were professional women—doctors and lawyers—who had fought sexism and discrimination while pursuing their educations and careers. Others were teachers or nurses, or had been, before they married. Wealthy society women became dedicated suffrage workers, bringing the experience and connections they had gained as club women, along with their social standing and financial strength to the suffrage fight.

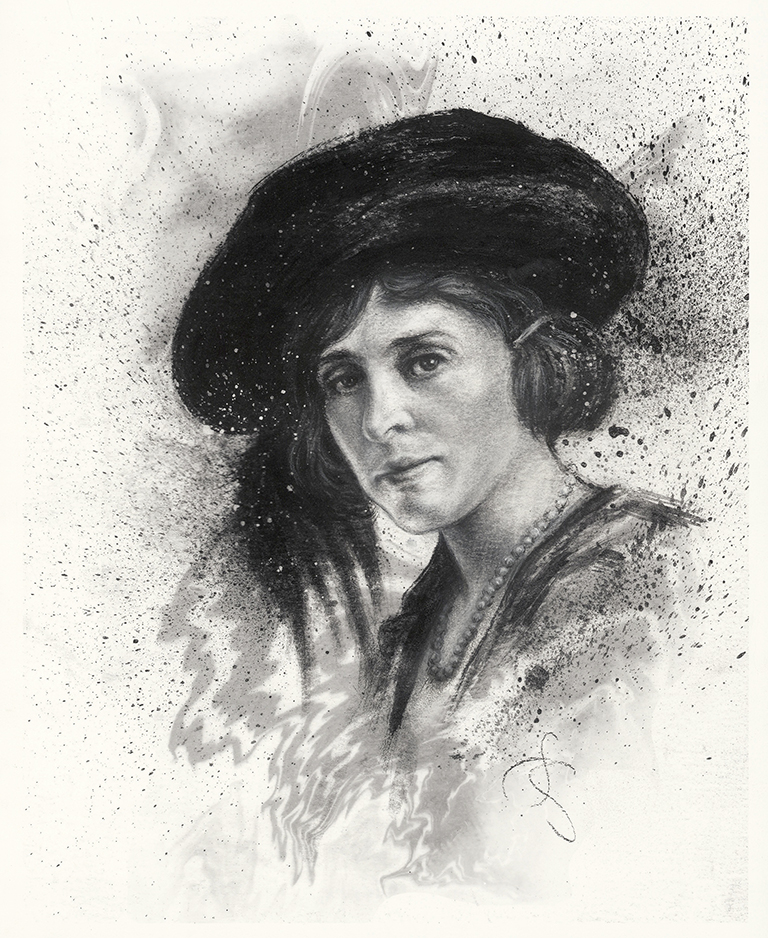

Featured image: Nellie Griswold Francis in the 1920s. Photo from Ramsey County History magazine, Winter 2017, article by Paul D. Nelson. Photo courtesy of MNHS.

Nellie Griswold Francis

Artist: Jennifer A. Soriano

Charcoal, ink, and gouache, 2020

Nellie Griswold Francis

Nellie Griswold Francis (1874-1969) was a club woman, a suffragist, and an advocate for African Americans. In 1914, she founded the Everywoman Suffrage Club for Black women in St. Paul. Their motto was “Every woman for all women and all women for every woman.” The club was affiliated with the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association. Francis was also a member of St. Paul’s Woman’s Welfare League. It is likely she was the only woman of color in that organization. Francis served as president of the Minnesota Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs and was on the board of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

I fail to see whence the American derives that feeling of superiority, which prompts him to refuse the Negro the panoply of citizenship equal to his own.

Francis grew up in St. Paul and was the only African American in her Central High School graduating class. She gave a graduation speech entitled “The Race Problem” and said, “I fail to see whence the American derives that feeling of superiority, which prompts him to refuse the Negro the panoply of citizenship equal to his own.” In 1894, she married William T. Francis, who graduated from St. Paul College of Law in 1904. They were the center of Black society in the city for about twenty-five years. In 1925, their Sargent Avenue neighbors voted for a resolution saying that “colored persons are not wanted in the district” and two crosses were burned on in front of the . They lived there for two years before moving to Liberia, where William served as the US Minister.

The Everywoman Suffrage Club became the Everywoman Progressive Council after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. In 1920, the Council arranged a mass meeting with members of the legislature in support of a state anti-lynching bill as a response to the lynching of three Black men in Duluth that year. Francis was probably the first Black woman to lobby the Minnesota state legislature. The bill passed.