The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution passed in Congress on June 4, 1919. It was ratified, or approved, by three-fourths of the states on August 18, 1920. In thirty-nine words, women gained the right to vote throughout the country. At that time, and still today, some states make voting more difficult for some African American, Native American, and newly immigrated and men.

The fight for women’s rights in the United States is as old as the country. In 1776 during the Revolutionary War, Abigail Adams wrote her husband, John, the President. She urged him to “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors . . .”

By the 1820s and 1830s, women spoke in public to fight for both the end of slavery and for women’s rights. Women like Lucretia Mott learned valuable leadership and organizational skills in the women’s rights movement.

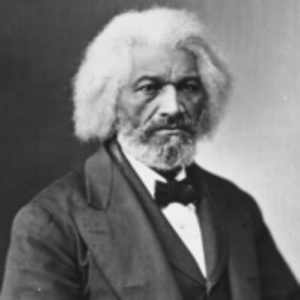

The Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention in the United States, occurred July 19-20, 1848. A group of Quaker women in the area worked with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and organized the event to include Mott. Stanton wrote a Declaration of Sentiments and eleven resolutions relating to women’s rights, including suffrage. Only one resolution passed. Many, including Mott, wanted to leave suffrage out. Frederick Douglass, the only African American at the convention, strongly supported it, and is credited with its passage.

Left to right: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglas

In 1869, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to win suffrage at the federal level. Months later, Lucy Stone and others formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). It focused on trying to change state constitutions. The two organizations merged in 1890 to become the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Featured image: Theresa Peyton.

Theresa Peyton

Artist: Klaire A. Lockheart

Oil on Canvas, 2020

Theresa Peyton

Theresa Peyton (1880-1929) was active in the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA). In 1912, she and others grew dissatisfied with how the organization was working throughout the state and formed the Equal Franchise League. This caused a rift between the women on the boards of the two organizations.

Peyton was elected president of the Equal Franchise League, which organized suffrage clubs throughout the state. She grew up in St. Paul in a working-class family and pursued higher education and a career. She was a teacher in the St. Paul schools in the early 1900s. She taught at Humboldt High School after she graduated from the St. Paul College of Law in 1909.

Through the years, she attended several national suffrage conventions and corresponded with prominent women and men in the suffrage movement, arranging for speakers to come to St. Paul.

Peyton volunteered her legal knowledge to help women and children through her work with the Protestant Women’s League.